Combining Musical Notation with Antiquated Notions

Invoking Victorian aesthetics

Explore

The Bizarre Voyage of Peter Harwood

combined with The Annotated Notes of Gerald Gredaltin

I asked myself: can music be experienced any other way than linearly?

I've always been a bit synesthetic (we all are, aren't we?); I see music and rhythm, but it has always bothered me that these images are fleeting—I can't sit and stare at them the way I would a painting, because they exist only in that sliver of present as the measure is being played, and then they disappear again.

In my explorations of how to remove the linearity of music, I first turned to Barber's Essay No. 1 for Orchestra. If Barber could write a piece of music based on a literary form, I reasoned, then I could compose a visual structure based on a piece of music. So I did. It looked like this:

I noticed all this mirroring that occurred in the piece as I drew it—mirroring I hadn't noticed from listening to the piece alone. After all, what goes up must go down. So, from there (naturally) I started to explore the idea of my structure being a giant ice formation, located somewhere on a glacier in the Arctic Ocean.

Someone had to find this structure, of course. If a giant ice structure exists in the frozen ocean and no one is there to hear it, then does it really exist?

I created the story of the intrepid 19th century English explorer, Peter Harwood, who would journey north in an adventure of unparalleled proportion, leaving his saddened love Mathilda behind as he set sail to find the music frozen in time.

Only it was paralleled.

Fully exploring the idea of reflection, I made the entire story mirror itself and then turn back around on itself from time to time.

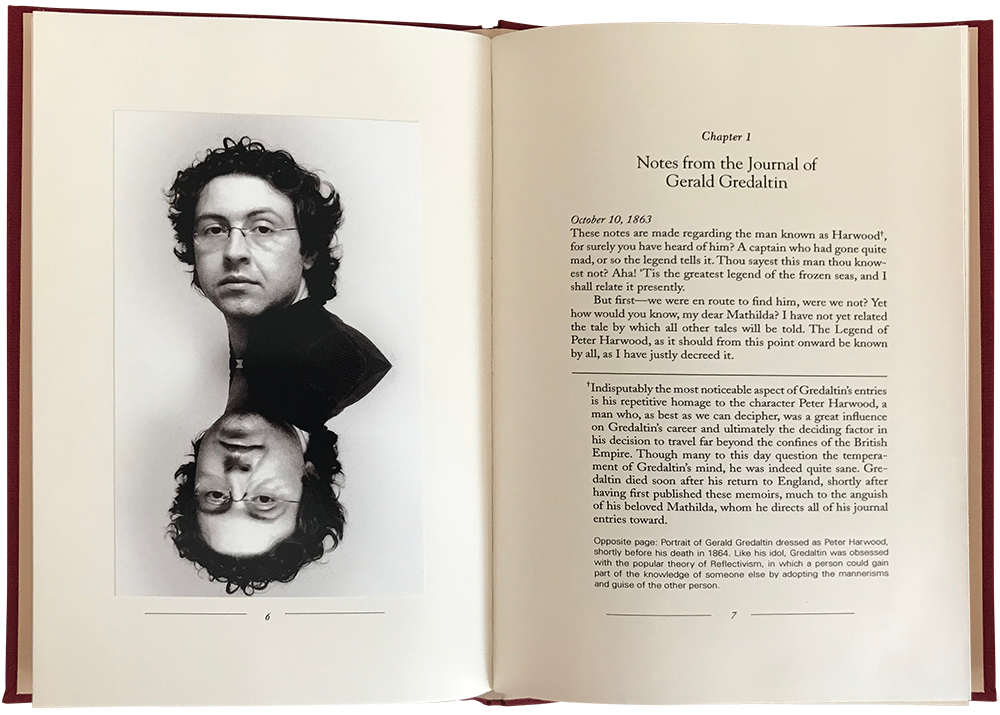

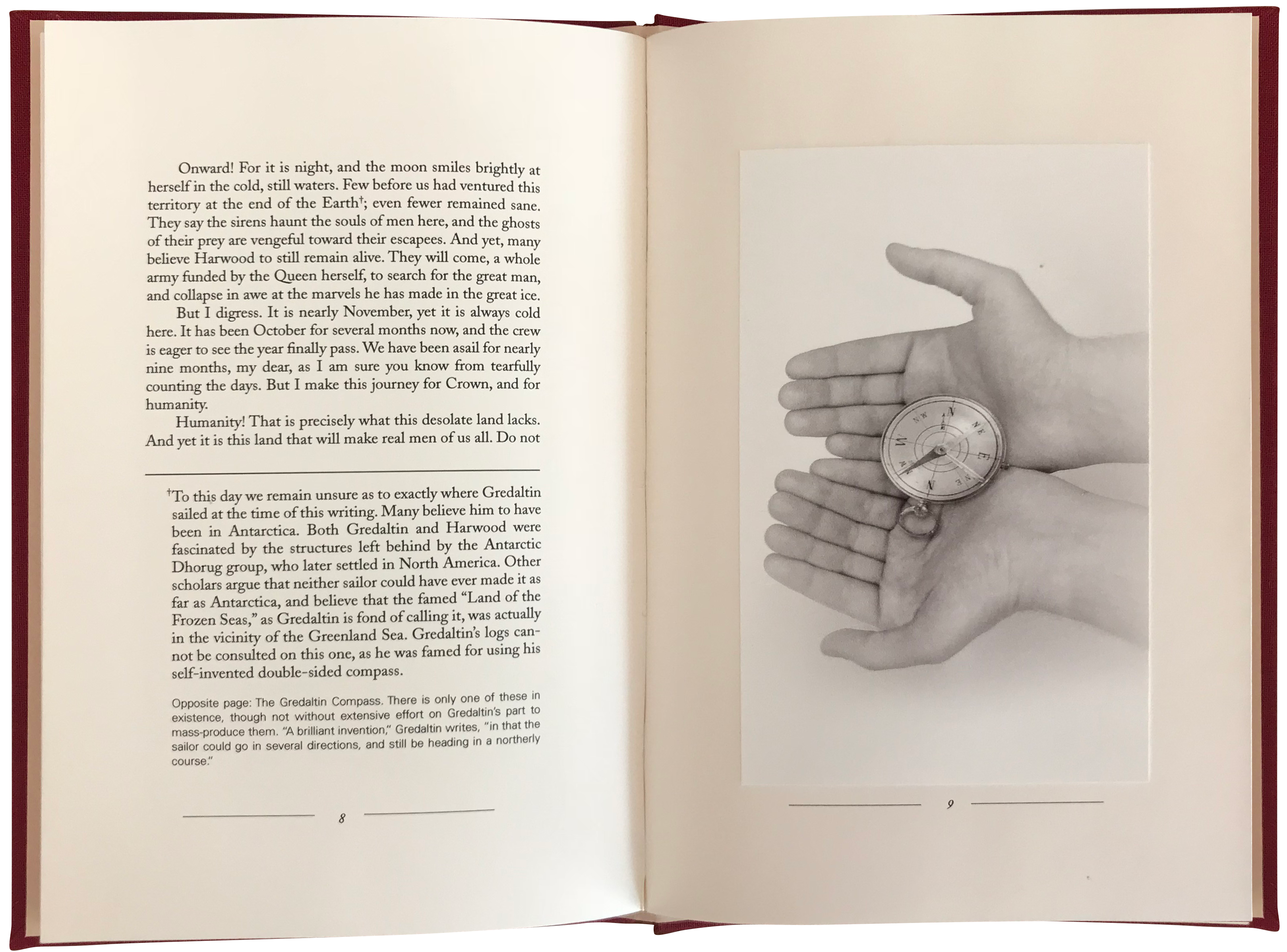

The book is told from the perspective of a Gerald Gredaltin, who is Harwood's mad alter ego. Gredaltin idolizes his real self and chases after his reflection in his own voyage toward Harwood's discovery.

Every image in the book is also reflected down the horizontal center of the page; the lower portion of each image is a bit, well, off. The text above the dividing line is Gredaltin's own writing (as he is writing about Harwood); the text below is annotated by an unknown hand that is, as the reader discovers, equally mad.

The images in the book are photos I took of myself and my husband, who has and always will put up with my shenanigans.

At this point, I realized there was no going back. So I made two more books.

The Tragedy at Bufordston, Illinois

"We've always thought of northwest Illinois as the edge of the world. We never thought it would also be the end of time."

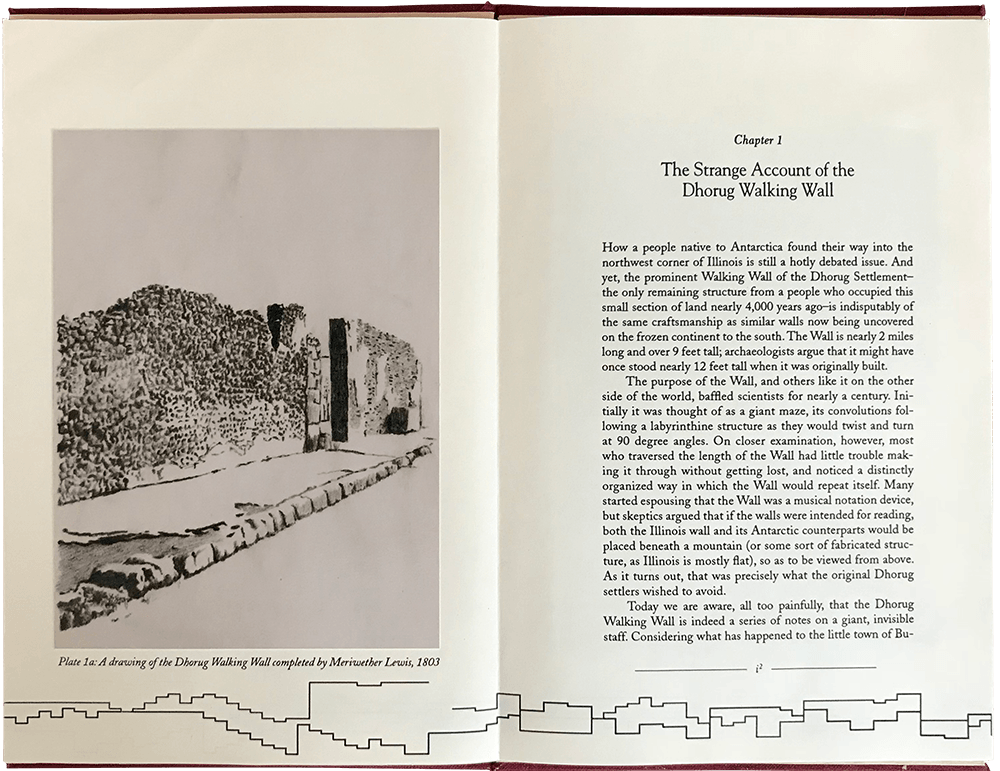

Thus dedicates the frontispiece for the second book, an accordion-bound tome that chronicles the dangers associated with completely removing the linear experience of music. Music is tied to time, I reasoned, so if you somehow figure out how to remove the experience of moving forward through a piece of music, you'll also remove the experience of moving forward in time. And you'll be stuck.

The book itself discusses a giant stone wall discovered in northwest Illinois that had been used by its builders to notate a piece of music through its bends and crevices; musicians would learn the piece by physically walking along the wall. When the well-meaning local tourism department decided to build a scaffold above the wall so that people could observe the entire wall at once, time in the small town of Bufordston stopped.

The book itself is created as an accordion so that it can be spread out and every page seen at once. If you turn the extended book over and look at the reverse side, you'll find almost the same story; however, like the Harwood/Gredaltin story, the images and the text are just a little bit different.

Many of the images in this book I shot (or drew) while wandering through what's left of Herculaneum and Pompeii.

The bottom of the pages are lined with The Concerto in D Minor for Two Violins by Vivaldi as it would look represented in a somewhat modified version of MIDI. I've always been fascinated by this piece of music because it seems the two voices never overlap in such a way as to drown each other out. And it's damn fun to play.

The Written Music of the Djosan Peninsula

Look closely and you'll see lines of text that are upside-down. Look closer, still, and you'll find some of the letters morphing into the musical notes of the Djosan musical notation system.

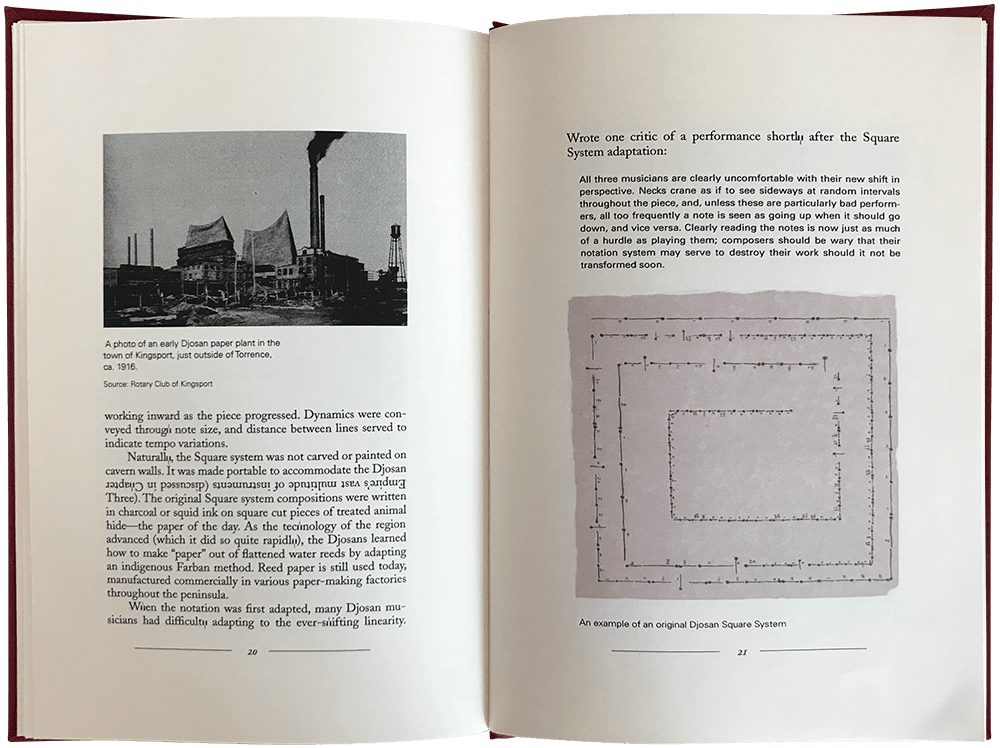

The images in this book I took from my home town archives and photographs I took while on an archaeological dig in southern Illinois.

I think I based the music in this book on Ases Tod by Grieg (from the Peer Gynt Suite 1). But at this point, does it even matter?