If you're a designer, especially if you are working with small or new businesses, you've probably encountered this dilemma: a client provides you with a gorgeous photo and asks you to include it on the front page of their Web site/brochure/book. When you ask for the original of the photo so you can get a better resolution, you're told the client just found it using an Internet search.

Well, if you know anything about copyright law, you know damn well you'd better not use that photo.

It is your responsibility as a designer to ensure you know the origin of every piece of media you insert in your clients' work. I'm not going to state that legally it's your responsibility (because I'm not a lawyer), but it's certainly your moral and ethical responsibility.

Copyright Law in a Nutshell

Disclaimer: I am not a lawyer.

According to the U.S. Copyright law, a work belongs to the creator of that work from the moment it comes into existence. This applies to recordings (audio and visual), written works, and any visual art. Therefore, even if a copyright wasn't filed for a particular image, the person who created that image owns the copyright for it.

So, that person that took that photo and pasted it on Facebook? Or put it into their Flickr album? Or blog? They probably never filed for copyright for the image. But they own the rights to it. And if you take that image and put it into a revenue-generating design, you technically need their permission before publication, and they can demand residuals for its use.

But isn't it my client's responsibility?

Technically, if you are doing "work for hire," you actually do not own the copyright for what you are creating; your client does. So, yes, the client is ultimately responsible for what is produced. However, here is where we get into the ethical responsibility. As a designer, you may be dealing with both large businesses with their own legal department, and smaller startups working in a basement with no knowledge of copyright law whatsoever. Both should know better, but both are also relying on you, the designer, to follow the law when creating work for them. It doesn't matter whether the client provided you with a bad image. It's still your responsibility not to break the law.

To put it another way, if your client gave you an image to use that was legal, but it was grossly inappropriate for the content, wouldn't you try to steer them away from using it? Or, if the client provided you with copy that was filled with glaring grammatical errors, would you not suggest they edit it before going to print? Sure, you're not a copywriter, but if you're the last one who touches the files before publication, you're the one who gets the blame if it looks like crap.

Finally, the last thing you would want is for your client to try to sue you for damages from any lawsuit they endured due to illegal use of copyrighted imagery. And, if you do have insurance against this type of backlash, you've already signed the form stating that you are versed in intellectual property law.

So where do I get legal images?

Client-generated imagery

Well, the best (and most expensive) option is to have the client generate the images themselves. This means hiring a photographer or illustrator to produce imagery that is specific for that clients' needs. This is usually termed "work for hire" as well, so even though the photographer or illustrator might be a separate entity, just like you, the client gains the rights to the work produced.

As an aside, it's also a good idea (and required by copyright law) for "work for hire" agreements to have a signed statement transferring the copyright of the producer to the client.

If you are the lead designer on such a project requiring this client-generated imagery, make sure you can attend the photo shoot, or have direct contact with the illustrator. This ensures the imagery generated perfectly fits in with your vision for the design.

My client won't hire a photographer!

Yes, this is expensive and many smaller companies don't have the funds. So, the next best option is stock photography

The best part about stock photography is it has become more and more affordable over the last 10 years. Whereas a royalty-free, print-ready image used to run ~$300, you can now get a quality image for around a dollar if you look hard enough.

Some popular stock photography sites include Corbis and iStock

Now, a word of caution before you run off and populate that Times Square ad with a discount stock photo: the cheaper the photo, the more likely it will be used by, well, just about everyone. Personally, I like to pay a little bit more for my images so I know I won't see the same image on everyone else's ad. But, if you have a small photo that is just filler on the back of a brochure, go ahead. Pay a buck.

Royalty-free imagery explained

Just because an image is "royalty-free" does not mean you own the copyright to it. When you pay for a royalty-free image, you buy a license to use that image without needing to pay royalties to the actual copyright holder.

It's important to read the fine print regarding these images when you purchase the rights to them. You can pretty much use them for anything, as many times as you want. However, there are certain restrictions (you usually can't use the image in a logo, for instance, or on a T-shirt design for mass distribution, or on a Web site template such as a Drupal or Wordpress theme).

Also, there may not be restrictions on how many different types of media you can use the image on, but there may be restrictions on how many times you can print a brochure that contains that image.

To see an example of how these rules work, the EULA (End User Licensing Agreement) for Corbis can be found here.

What's Rights Managed?

If you need to ask, you don't want to use these types of images. Basically, there are many more restrictions on how you can use these images, and the fees are much, much higher. If you need a photo of the President, then you would use a rights managed (RM) photo. Otherwise, stick to royalty-free (RF).

On that note, if you are responsible for the art buying for your client, make sure you comp your design using only RF photos. You wouldn't want your client to fall in love with a RM photo, only later to be told it's $6,000 to use.

But this Google search image is perfect!

I'll admit, there have been times I needed something very specific that I could not find on a stock photography site, but I could find on Flickr. Well, what I tell my students when this happens is, find the generator of the work and simply ask what it would take for you to get a license to use their photo.

If the image has been taken by a professional photographer, no doubt they are familiar with licensing agreements, and might have one they can draw up for you. Make sure proper contracts are drawn and fees are paid to the photographer. If you simply want to use the image in a school assignment, for a blog, or for some other non-revenue generating design, the photographer might be willing to let you use the image for free (never hurts to get that in writing, however). But, you do need to ask.

Along those same lines, if you want to use a RF image for a project and you are unsure if the license agreement covers how you want to use the image, contact the stock photography site directly. They will be happy to put you in touch with a personal representative, who can answer your questions about usage.

Repurposed from an article I originally published in 2014.

Article directory:

3 Simple Ways to Edit PDFs

Take charge of your files without having to bother your designer

Read more >

4 Common Mistakes When Using Line in Design

Lines have meaning. Use them correctly or look like a buffoon.

Watch Video >

5 Quick Tips for Using the Pen Tool

Nobody likes the pen tool on the first ten tries. These tips will make using it less painful.

Watch Video >

Your own POPs and PODs

Create your personal design brand using marketing principles.

Read more >

What I tell students when they say they want to freelance

Spoiler Alert: I usually try to talk them out of it.

Read more >

What I miss about Web design of the '90s

Web design has come a long way since the last century, for better or for worse.

Read more >

Semiotics in typography

There is a reason the shape of a serif makes you feel that way.

Read more >

An introduction to Gestalt principles

Know what it's really all about.

Read more >

To barter or not to barter

Here are some general guidelines to follow to ensure relationships emerge unscathed.

Read more >

On spiders

A critical analysis of why these creatures strike horror into our hearts.

Read more >

An homage to geometric sans signage

These typefaces became the embodiment of the Modern era.

Read more >

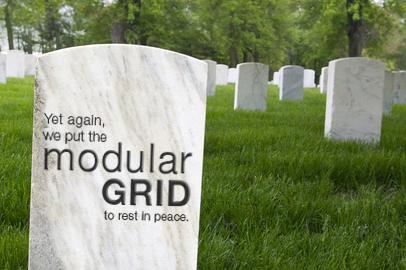

The centered text takeover

A hopeful eulogy for the modular grid.

Read more >

Copyright and Imagery

Know the origin of those images, and know the licensing agreements therein.

Read more >