I just discovered a colossal spider nestled in his self-spun web at the top of the exterior of my bedroom window, and his girth was made ever more gruesome by the fact that he is missing three arms.

If you’ve read some of my fiction you might think I have a sick fascination with bugs. This really isn’t the case; they absolutely terrify me. Granted, my first instinct when I saw this guy was to stand on a ladder so I could identify just how his missing appendages had been dismembered, but, in my defense, my second instinct was to run in terror. What the hell was that beast doing there? On my window pane?

I have actually never written about arachnids as a figure of horror (until now), but I do admit that they terrify me. With good reason. I’ve had my share of venomous bites, and have heard stories from acquaintances about even more serious encounters. I have a healthy fear of this creature because he can actually harm me (again)—and there is always the fear that the next time won’t clear up with a simple dose of antibiotics. Those of us who grow up in rural areas are formally educated about which of nature’s individuals can cause illness or death, and certain eight-legged brutes top the list.

However, should that terror extend to the simple wood spider that comes in from the cold at first frost and helps to reduce my six-legged population? Was this unnatural fear stemming from cultural or natural influences? I had to look this up.

My first stop was The Journal of Victorian Culture. I can’t tell you how much Victorian horror has influenced my own life. Nothing gets the nightmares going like being a young child and getting your hands on a collection of 19th century English ghost stories. And, of course, there’s no denying Victorian horror is still alive and well in contemporary literature on a global scale. Our decades-long literary dance with cybernetics, genetic modifications, and artificial intelligence mimics the Victorian fascination (and wariness) toward industrialization and the fear of playing God. And, of course, vampires. Vampires, vampires, vampires. Look to the original. Bram Stoker’s original tome is just as sexy as any young adult macabre romance of this century. But I digress.

Claire Charlotte McKechnie has written a fascinating article entitled "Spiders, Horror, and Animal Others in Late Victorian Empire Fiction" (Journal of Victorian Culture) in which she tracks the cultural attitudes toward the spider from the 17th to the 19th century, and shows us that the peaceable spider didn’t gain notoriety as a creature of horror in British literature until the mid-19th century. She argues that the poor spider becomes a metaphor for The Other, and, of course, the narrow Victorian attitude toward the rightness of imperialism meant that all things un-British were seen as captivating, wild, but ultimately wrong. Combining Victorian imperialist views with contemporary reports of many different species of spiders in lands beyond the British Isles—some of which were venomous—led to creation of the spider as a symbol of horror, wrongness, and otherness. Of course, that’s if I understand her article correctly. Not like I’m a scholar of this stuff or anything.

I think Stephen Asma’s easy-to-find paper Monsters on the Brain: An Evolutionary Epistemology of Horror does a nice job of complementing McKechnie’s article. Asma argues that research has shown we are evolutionarily programmed to fear snakes, spiders, and other venomous creatures, but that that fear may not necessarily come from an innate knowledge that these animals are dangerous—instead, it comes from a natural fear of things that are vastly unlike us. (I really enjoyed his shout out to the facehuggers of Alien—creatures that combined snakes and spiders into one horrific organism). This fits nicely with McKechnie’s analysis that the spider came to symbolize The Other in Victorian horror. But it also implies that the spider hadn’t necessarily been twisted into the symbol of The Other, but rather, The Other had been twisted into the visage of a terrifying, unnatural spider. Asma goes on to speak of how this inborn fear of things that are different has led to the wariness that we often experience when encountering a new culture, and, in order to overcome that fear we must actively unlearn our reliance on these fears. Words of wisdom. It does seem that, if you pay attention to that gut feeling that something’s wrong, you can learn to identify which fears stem from something because it is different, and which fears manifest because something is genuinely dangerous. But that distinction takes a great deal of open-mindedness and self-scrutiny—two things the Victorians were not known for. We could all write volumes about how Victorian attitudes have warped global culture irreparably.

But then again, what do I know? I could just be some hack with an Internet connection and a cup of tea.

In the meantime, as I read these articles, my poor massive five-legged spider has come to seem less and less terrifying, and more a representation of resilience, subjugation, and inner beauty. Could I possibly fear this survivor merely because his skeleton is on the outside of his body instead of inside? Thank you, Asma and McKechnie, for changing my own perceptions toward massive arachnids.

Postscript: The next morning, I woke up to find the previous evening’s storm had washed my quenquepedal friend away. I was actually saddened to find the remaining strands of his lopsided web, wafting in the breeze, its previous inhabitant nowhere to be found.

Article directory:

3 Simple Ways to Edit PDFs

Take charge of your files without having to bother your designer

Read more >

4 Common Mistakes When Using Line in Design

Lines have meaning. Use them correctly or look like a buffoon.

Watch Video >

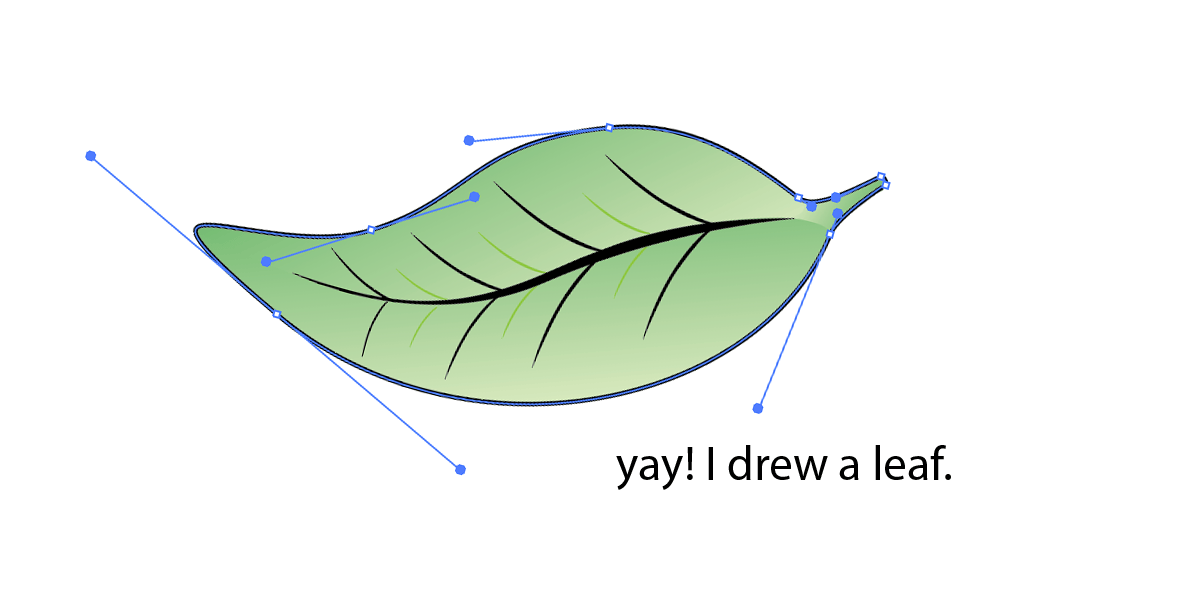

5 Quick Tips for Using the Pen Tool

Nobody likes the pen tool on the first ten tries. These tips will make using it less painful.

Watch Video >

Your own POPs and PODs

Create your personal design brand using marketing principles.

Read more >

What I tell students when they say they want to freelance

Spoiler Alert: I usually try to talk them out of it.

Read more >

What I miss about Web design of the '90s

Web design has come a long way since the last century, for better or for worse.

Read more >

Semiotics in typography

There is a reason the shape of a serif makes you feel that way.

Read more >

An introduction to Gestalt principles

Know what it's really all about.

Read more >

To barter or not to barter

Here are some general guidelines to follow to ensure relationships emerge unscathed.

Read more >

On spiders

A critical analysis of why these creatures strike horror into our hearts.

Read more >

An homage to geometric sans signage

These typefaces became the embodiment of the Modern era.

Read more >

The centered text takeover

A hopeful eulogy for the modular grid.

Read more >

Copyright and Imagery

Know the origin of those images, and know the licensing agreements therein.

Read more >