I’ve had my toe (okay, maybe my foot) in academia for the past eleven years, so I’ve had many opportunities to interact with young, talented designers about to venture out into the world on their own. As they prepare for that final portfolio presentation or department-wide critique, I always ask them about their post-graduation career plans.

Invariably, a significant portion of them will respond with "I want to freelance. You know, do my own thing."

And then they follow up with "so, just how do I get clients?"

So I, the seasoned cynic, respond with:

"You don’t. Go get a job."

They pout. They think I don’t believe in their talent or their drive. Or, they list all the clients they currently have, which usually consist of their church, a friend who’s starting a business and a family member who needs a logo. Which is great, yes. But not enough to sustain a career on. And not enough to start a career on, either.

Because, they haven’t yet had the years of full time employment that they need in order to actually launch that successful freelance career.

@thegiantthinker recently posted similar advice on AIGA’s site. The AIGA article suggests a healthy career of 6–8 years prior to trying to freelance fulltime. I did 6 years, and it worked out, but I think it would have been much easier if I had stayed in-house for 10.

Why is full time employment a necessity in this field? I could go on and on, but I’ll reign in my inner professor and limit it to two key points that I can personally attest to:

1. Successful designers need to have the mentorship that comes with working with others, and

2. Successful freelancers need a long history of steady employment in which to build up their network and reputation

Mentorship

Mentorship, schmentorship. Isn’t that what design school is for? Whether you’re fresh out of school or you’ve been doing this awhile, you remember the long nights, the 5am inspiration that pushed your project to completion, the soul-piercing critiques, the knowledge that your work would be crushed and stomped on repeatedly until you were ground to nothing, and then you would emerge, that beautiful phoenix with design skills that could conquer the real world.

But the real world isn’t design school. And mentorship isn't necessarily a professor giving advice. It's also the caring co-worker who helps you navigate a proprietary FTP interface.

I was fortunate enough to land an amazing job right after undergrad, working as an in-house graphic designer for a children’s literacy publication. We made supplemental materials for schools and worked with teachers on professional development. Fun work, great co-workers, damn fine job. I felt like I fit right in.

But I hadn’t been there long before my inexperience started showing through. My disks (yes, we were still using zip disks) started coming back from the printer with errors, and as a result my jobs were going to press late. I was shocked—what errors? I knew how to package a Quark file (yes, we were still using Quark) for print, I knew not to mix PMS colors into a 4C job. But I wasn’t completely clear on the difference between a T1 and a TT font, and I didn’t yet know how to print camera-ready separations. It was all those little nitty-gritty details that I didn’t know that I had to learn, and I had to learn quickly, and I probably wouldn’t have learned if I hadn't had awesome co-workers who were willing to sit down and show me.

Yes, I know the world of design has changed. We haven’t had a client ask us to provide separations in nearly five years. But the breadth of knowledge you need to be successful is still just as vast. Design school teaches you theory, methodology, and tools. But there’s not enough time to teach every single detail (I actually didn’t get a design degree until my MFA, but I’ve taught at the undergrad level enough to know). And, because the design world does change so quickly, the skills you picked up your first year there might be different by the time you graduate. Getting into a job, getting up to speed, and then moving at the pace of design is the only way to survive.

Networking

You need to formulate connections in order to get freelance work. It’s not just about going to the Chamber of Commerce meetings and handing out your business card, or making 200 leave-behind Slinkies with your logo on them (don't laugh—I've done that one, too). Design is expensive, it’s subjective, and a lot of people do it. Why should any business, large or small, choose you over all the other eager, bright-eyed designers pushing their portfolios onto them?

Because they know you already. They know you because they’ve worked with you, somehow, somewhere, in the past. And they know they want to work with you again. That kind of network of people who know you and have worked with you comes from work experience. Lots of work experience.

If you haven’t formulated those connections, you’re in for a long road, far tougher than the qi-shattering journey you just went through in design school.*

If you’re about to graduate and considering a full-time freelance career, I hope I’ve talked you out of it. If not, please email me and I’ll persuade you further.

*The only exception to this advice (and I’ve known one or two who have done this) would go to individuals who have actively built up a network during college, worked in highly visible roles for other companies, maybe even delayed graduation to build client lists. But people who can successfully pull that off are rare, off-the-charts talented, and have chutzpah of steel.

Article directory:

3 Simple Ways to Edit PDFs

Take charge of your files without having to bother your designer

Read more >

4 Common Mistakes When Using Line in Design

Lines have meaning. Use them correctly or look like a buffoon.

Watch Video >

5 Quick Tips for Using the Pen Tool

Nobody likes the pen tool on the first ten tries. These tips will make using it less painful.

Watch Video >

Your own POPs and PODs

Create your personal design brand using marketing principles.

Read more >

What I tell students when they say they want to freelance

Spoiler Alert: I usually try to talk them out of it.

Read more >

What I miss about Web design of the '90s

Web design has come a long way since the last century, for better or for worse.

Read more >

Semiotics in typography

There is a reason the shape of a serif makes you feel that way.

Read more >

An introduction to Gestalt principles

Know what it's really all about.

Read more >

To barter or not to barter

Here are some general guidelines to follow to ensure relationships emerge unscathed.

Read more >

On spiders

A critical analysis of why these creatures strike horror into our hearts.

Read more >

An homage to geometric sans signage

These typefaces became the embodiment of the Modern era.

Read more >

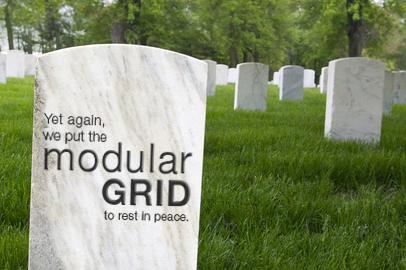

The centered text takeover

A hopeful eulogy for the modular grid.

Read more >

Copyright and Imagery

Know the origin of those images, and know the licensing agreements therein.

Read more >